Part I by Fr. Robert Maloney, C.M.

Part I by Fr. Robert Maloney, C.M.

More and more, as his life went on, St. Vincent pondered the mystery of God’s providence. Trust in providence became one of the keystones in his spirituality. He writes to Jean Barreau in 1648: “We cannot better assure our eternal happiness than by living and dying in the service of the poor, in the arms of providence, and with genuine renouncement of ourselves in order to follow Jesus Christ” (SV III, 392). Vincent was utterly convinced that for those who love God and seek to do his will, “all things work together for good” (Rom 8:28). He tells Louise de Marillac: “In the name of God, let us not be surprised at anything. God will do everything for the best” (SV III, 213). Vincent believes that God governs history and that nothing eludes his power, that there is a guiding plan, beyond our comprehension, which gives meaning to life’s events. For Vincent, those who trust in providence find meaning in the polarities of human existence: light and darkness, grace and sin, peace and violence, plan and disruption, health and sickness, life and death. Vincent stood with reverent trust before the mystery of God, as revealed in Christ, in whom life, death and resurrection are integrated. Vincent […] trusted deeply in God’s “hidden plan” (cf. Col 2:2-3), even as he experienced the death of missionaries he sent to Madagascar, the religious wars in Lorraine, the connivings of Cardinal Mazarin, the turbulent masses of neglected poor in Paris.

This Advent I encourage you to ponder the mystery of providence, both in your own life and in the wider history of humanity today. Do we, like St. Vincent, trust deeply that a loving, personal God guides each of us as well as the events of contemporary history, even the tragic ones? That is surely an enormous challenge as we see wars and threats of war, continued terrorist attacks, and forms of poverty and sickness that human resources today really could overcome, but that the will of the world fails to tackle.

Part II from Reflections by Ross Reyes Dizon

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (a participant in the German Resistance movement against Nazism, executed by hanging in April 1945) affirms that faith demands that the believer depend solely on God’s justice or grace, which is what it means to throw oneself into the arms of God and to watch with Christ in Gethsemane. This is, of course, no more than an admission that the Christian is not justified on the basis of his works; God credits to him righteousness apart from works (Rom. 4:1-6).

But this admission sounds to me more convincing, and the Pauline teaching certainly more credible, coming from someone who works and suffers and dies working—which was the case with Bonhoeffer—and not from a quietist who, stressing the exclusive efficacy of grace in a corrupt world and advocating total abandonment to God’s action, tries to flee from the world and remains passive. While the former highly values grace and sees it as “costly,” since it demands that the disciple deny himself and take up his cross, repent and radically change in order to live according to the gospel, the latter undervalues grace, making it “cheap,” that is, something that is suited simply to one’s likes and dislikes. One who works hard and yet acknowledges that everything depends on God, such a one, in my opinion, proves himself to be an authentic person in whom there is no deceit, given that he does not escape from such responsibilities as sharing one’s cloak or food with the person who has none—all of which, I think, supposes conversion and fundamental option for the good.

The story is told that one day, upon receiving from the community treasurer the bad news that the resources were all but gone and there was no money left for the relief of countless folks fleeing from war and displaced by it, St. Vincent replied: “That’s good news. Now we can show we trust God.” And money arrived within the week.

Indeed, the saint depended on God’s providence, he threw himself into the arms of God, he watched with Christ in Gethsemane. Surely, he knew great peace and his spirit deeply rejoiced in the Lord. It’s now our turn to do and be as did and was St. Vincent, even as we come upon “hard times” beyond our control.

Part III by Fr. Robert Maloney, C.M.

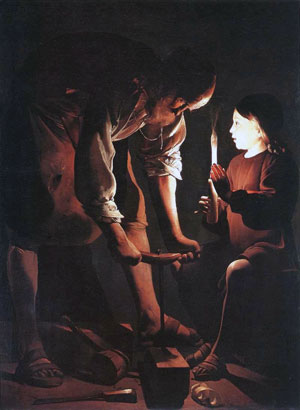

St. Joseph, the Carpenter by Georges de La Tour

It is clear in Matthew’s gospel that Joseph stands, with eager expectation, at the threshold of transcendence. From the darkness of his own limited understanding, he is continually peering into the mystery of God. Surely he cannot fathom the virginal conception of Jesus that the angel announces, but as a “just man” (1:21) he tempers the strict observance of the law with loving compassion and bows in reverence to God’s incomprehensible ways. Surely he does not understand how this child, who seems like any other, could be “God with us” (1:23), but he abandons himself, in faith, to the task of loving the child and educating him. There is something very beautiful about Joseph’s contact with the transcendent mystery of God. He was not a monk. He did not live a life cut off from ordinary daily contacts with the world. In fact, he was a carpenter (Mt 14:55), a neighborhood craftsman who did woodwork and made furniture, and he raised his son in the same trade (Mk 6:3). Yet in the midst of his daily manual labor and family life, Joseph was surrounded by the mystery of God and he penetrated it with faith. He trusted in God’s daily providence. He believed in God’s revealing word. When he read the signs of God’s will, he rushed to put them into practice.

With Matthew’s Joseph, I want to urge you this Advent to gaze into the mystery of God with courage. I say “with courage,” because it is no easier for us to believe than it was for Joseph. Many of the outward signs that he saw seemed to contradict the promises that God was making to him. It is often that way for those who serve the poor. While there are many joyful moments in our ministry, there are also dark, fearful ones. The beatitudes tell us “happy are the poor,” but we often see them oppressed and beaten down by injustice, as in Mozambique, Albania, and many other places. The word of God says that “the meek shall possess the land,” but we often witness violent, even fanatical, strife that takes the lives of countless innocent non-combatants, as is occurring in ex-Yugoslavia and Rwanda. The gospels tell us that “those who are persecuted for justice sake will inherit the kingdom of God,” but we often observe, as in China, that persecution is long, painful, and discouraging. Joseph knew similar experiences. He knew the pain and embarrassment of poverty when there was no room in the inn and he had to place his infant child in a manger. He witnessed violence when Herod unleashed his wrath against children in Bethlehem. He felt persecution, when he fled to Egypt with Mary and Jesus, and later to Nazareth. Yet he believed. He believed that God walked with him, that God is faithful to promises, that God is alive, that we can find God not only in the light but also in the darkness. He lived on the edge of mystery and was not afraid to gaze into it with courage in order to find God.

Advent is upon us. Imagine how Joseph felt as the birth of his mysterious son approached: puzzled, excited, awed. Yet, in his puzzlement, this carpenter of modest means had enormous resources. The word of God was his strength. Deep faith was his light in the darkness. It enabled him to see the presence of God even where suffering, privation, and violence appeared to reign.

If love for God’s word and lively, penetrating faith were indispensable tools for Joseph the carpenter, they are likewise so for all of us missionaries.

I pray that this Christmas time will bring you abundant peace and joy in the Lord.

Your brother in St. Vincent,

Robert P. Maloney, C.M.